. . . The PingFang Book . . .

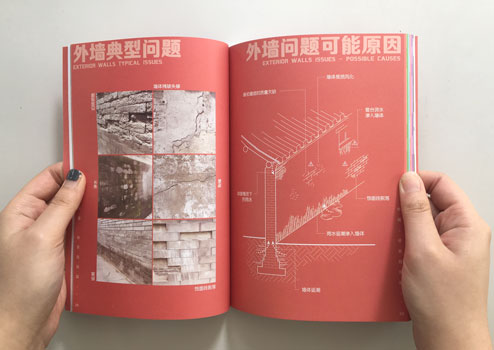

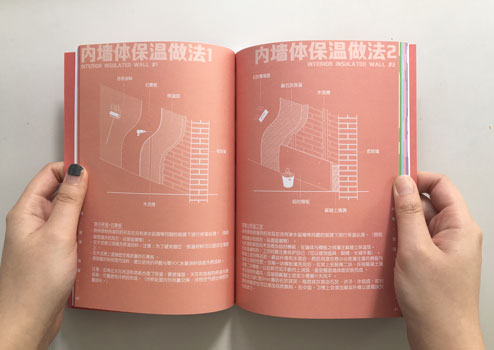

To live in a house, big or small, right in the middle of the booming Beijing metropolis is by any account exceptional. To be surrounded by buildings that embody the efforts, beauty, and intelligence of past generations is something each of us should be proud of and feel responsible to protect. Yet, not everyone lives in a palace or a pristine Siheyuan and hutong life can be one of many challenges and hardship. Most of us live in little ping fangs, historical or not, traditional or not, nice…or not. Spaces are small and congested, structures are sometimes insalubrious, in need of constant repairs, amenities are insufficient, comfort is… limited. Years after years many of our houses have suffered successive damages that seem extremely difficult or too costly to repair. Previous repairs were sometimes inadequate either because the material used were of bad quality, or the execution lacked expertise. Time and again, we tried to patch-up our houses’ problems without actually understanding and treating the source of the matter. Modern materials, although cheap and readily available, are sometimes inadequate for the hutongs particular situations and prove to be ineffective solutions. Traditional techniques, on the other hand, are sometimes difficult to apply and do not guarantee the level of comfort needed nowadays. The lack of information on proper ways to assess where the problems are and what are the best ways to resolve them is further exacerbating our inability to responsibly and effectively repair our homes.

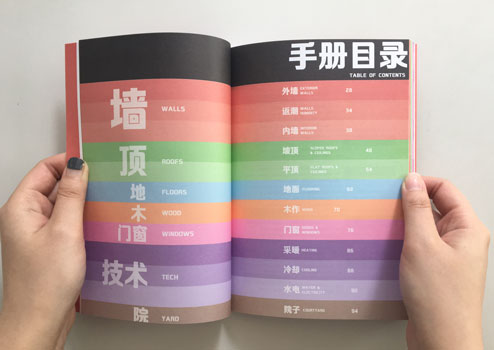

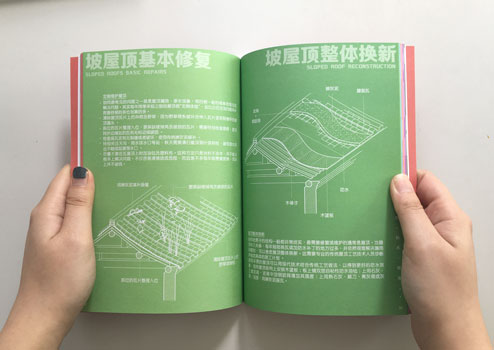

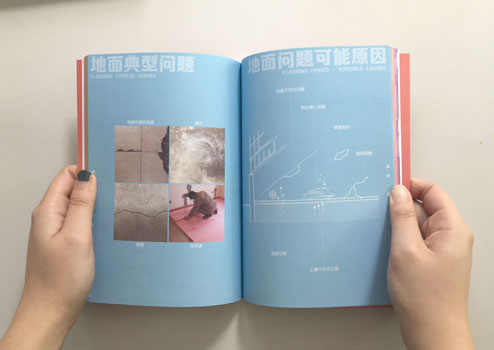

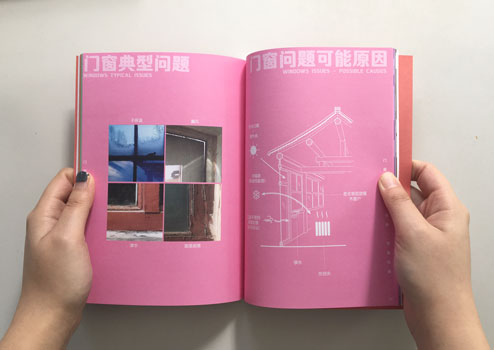

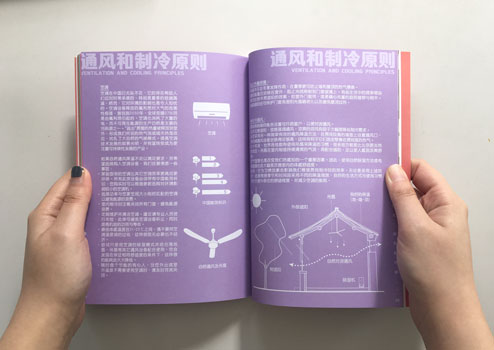

Where’s the problem? How can it be fixed? What are the best materials to use? What are the required expertise and know-hows? What are my options? These are some of the questions the Ping Fang Book (Beijing hutongs houses low carbon renovation handbook)tries to wrestle with.

The handbook is dedicated to the long-standing hutongs inhabitants and the newcomers, to the laobaixings and the new generations that decide to settle in the city’s oldest districts. It is an attempt at stimulating a more positive take on urban renewal for the inhabitants, by the inhabitants. It is grounded in a sincere admiration for the qualities of an exceptional part of the city that is made of supposedly ordinary, supposedly dilapidated, supposedly problematic, small houses. It touches upon notions of historical preservation but avoids only focusing on traditional typologies. Whether you live in a traditional structure or a more recent construction, it tries to integrate the multiple realities and the variety of situations we face in the hutongs. It puts forward extremely down-to-earth ideas on how to cope with houses that need constant tending, maintenance and care. It tries to demonstrate that it is possible to improve while preserving and that it belongs to each of us to value our homes and build upon their prevailing qualities.

The handbook is freely downloadable HERE in English and Chinese:

The PingFang Book _ English version :

平房手册 (下载) _ Chinese version :

Preface extract:

ON PRESERVATION

Anyone with a basic understanding of the last 40 years of onslaught on Beijing’s hutongs will agree that preservation is a must. But what exactly are we trying to protect and how exactly are we going to do it? Are we choosing to only preserve the remnants of a lost traditional epoch? The chosen fragments that are deemed historically significant? Or should we preserve everything? Are we trying to go backward or forward? Are we trying to safeguard a culture that we see as being endangered? Against what? Who are the key actors of this preservation? Who decides? What is the purpose? For whom?

Heritage shouldn’t be limited to a simplistic understanding of tradition or to the preservation of first-rate cultural relics, it’s in the small things, in the everyday, in the vernacular, in the exceptions as well as in the norm, in the people as much as in the built structures. It is multilayer and multi-epochs, it traverses time. History isn’t and never has been a fixed concept; history never stopped. The idea that there was a specific moment, a clear-cut date at which the hutongs were a perfectly harmonious urban fabric, an “original state” that we should strive to recover, seems ludicrous at best. This reasoning dangerously implies that any later action or transformation performed on this supposed “original” is viewed as a mistake, a historically invalid, if not subversive, urban development. The mutation of the traditional hutongs into the current ad-hoc, sometimes messy, sometimes irrational, but also sometimes extremely pleasurable urban fabric, cannot in our opinion be considered a historical incident, an error in the city’s evolution. It could be understood instead as an expression of the extraordinary inventiveness, resilience, and active commitment of its people toward their living environment. Any action that negates this incredible richness in the name of preservation is reactionary. The demolition of the existing physical, social and cultural structure of the city we’ve witnessed in the past years for the rebuilding of an idealized past seems utterly counterproductive. Additionally, it’s also been incredibly offensive, not to say violent, towards the hundreds of thousands of people who live in the hutongs, maintain them, transform them, and deeply cherish them. Preservation shouldn’t be a limitative process, something that relentlessly tries to go back to some nostalgic idea of a supposedly lost urban splendour. It should be an empowering process, an opening up of the rich, diverse and extremely complex heritage of the city. Part of this rich heritage is the way inhabitants have actively engaged with and transformed the historical city into the incredibly exciting urban space it is nowadays.

That said, let’s avoid being too romantic. In many ways, the hutongs are in a state of alarming decay. We, the hutongs inhabitants, for reasons that might have been pragmatic at one point, have too many times acted crudely on our dwellings and our city. Choosing the easiest quickest solution to temporarily fix an issue, our negligence has resulted in a gradual loss of some of the hutongs best qualities. If the city’s preservation and its evolution are to be considered as collective undertakings where each of us have a potential crucial role to play, the responsibility not to self-sabotage falls on all of us. It belongs to each inhabitant, each person repairing or transforming their houses, to think more carefully on how they can increase their comfort in old structures without losing their inherent architectural qualities. It might sometimes be a bit costlier, sometimes a bit more complicated to plan and execute, you might even have professional builders telling you that you’d better get rid of the old and renew or cover-up everything. Still, there are many ways this can be done without even being technically or financially too demanding. The question isn’t to adopt a rear-guard conservationist point of view declaring that older structures shouldn’t be touched and condemning new modern constructions in the hutongs. On the contrary, new is good but… so is old! Yes, things might have got damaged and yes, we have to find ways to provide modern standards of comfort in ageing structures. But we cannot throw the baby out with the bathwater nor can we carelessly slap temporary Band-Aids on our issues. We need to make our homes better by combining the virtues of contemporary know-hows with the qualities of the past.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .